Current Literature on ICHRAs

ICHRAs are a hot topic. Not only have many companies raised a lot of money recently to “reinvent health insurance” by administering ICHRAs, but early versions of the One Big Beautiful Bill (BBB) Act included a tax break for businesses that offered ICHRAs.

This combination of events has made ICHRAs a hot topic on my LinkedIn feed. The general lack of substantive discussion about the mechanics, history, and system-level impacts of ICHRAs have frustrated me as someone who likes to dive into the details of how health insurance works.

In this post, I aim to give you enough context to understand the ICHRA landscape from both the micro and the macro perspective. You will understand both how an individual ICHRA plan operates and the role that ICHRAs play within the broader topic of healthcare financing.

I am in a unique position to explain ICHRAs:

I set up and administer an ICHRA for my small business, managing legal, compliance, and payroll in-house (without a platform).

See instructions later in this article for notes on how you can set up your own ICHRA without adding a middleman.

My day job is paying health insurance claims and doing customer service for over 100 small businesses’ health plans.

My cofounders and I considered starting an ICHRA administrator three years ago, however determined that the product did not really solve a real problem for customers. Instead we chose the path less traveled in becoming a full Third-Party Administrator.

Section 1: Why do businesses provide benefits? A Background on Employer Health Insurance Tax Incentives

Have patience. We will not yet get to ICHRAs in this section but you need to understand this. Otherwise you become one of those thirsty-for-a-trend brokers who just hashtag random things on LinkedIn.

Why do businesses provide health insurance benefits?

Most people in the United States get health insurance through employment (either their employment or the employment of someone in their family or their former employment). This system is entrenched in the US tax code which has since the 1950s allowed businesses to provide healthcare benefits to employees in a tax efficient way:

Although benefits are essentially compensation for employees, businesses do not have to pay payroll taxes on this spending.

Employees also do not have to count the value of these benefits towards their taxable income.

This may seem insignificant, but it makes a huge difference for workers who on average have a marginal tax rate around 30% and are given benefits worth $10k+/year.

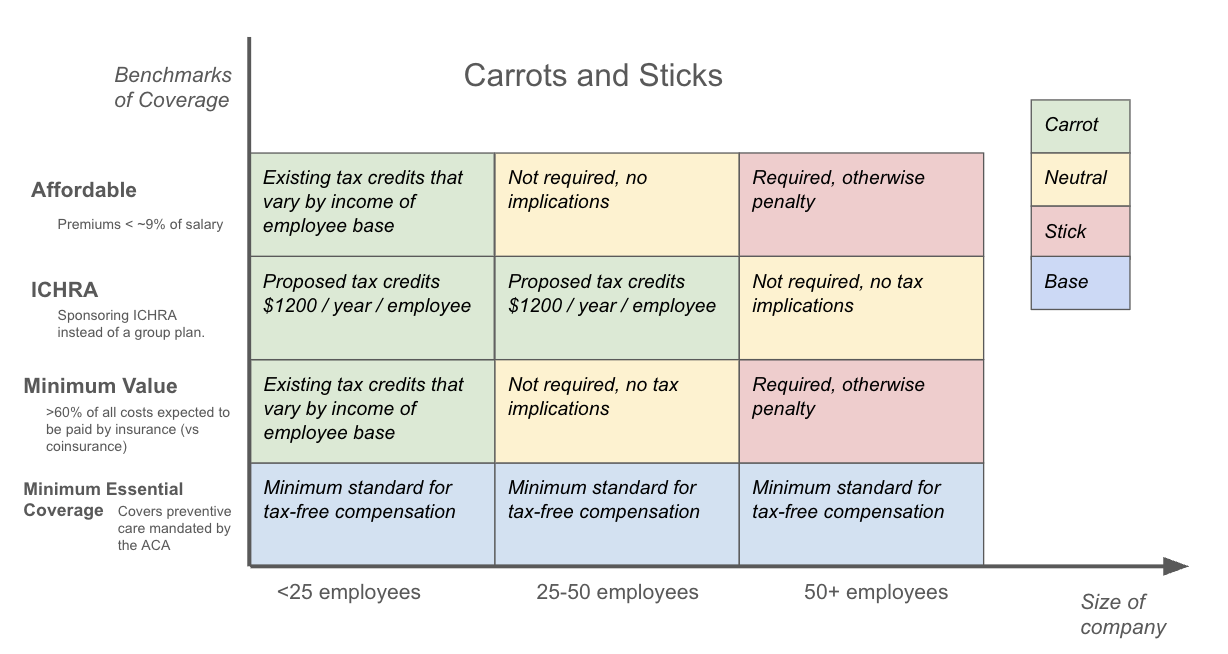

Despite everyone realizing that this distortion is probably bad, laws and regulations over the years have further entrenched health insurance and employment by adding additional carrots and sticks into the equation.

Carrots (additional tax incentives) have been added to reward small businesses who provide health insurance benefits

Sticks (penalties) have been added to penalize large businesses who don’t offer health insurance benefits.

Sidebar: The controversial “Individual Mandate” provision of the ACA used to penalize individuals who did not have health insurance. Although this mandate is technically still around, the current penalty for not having insurance is $0. The business penalties are still around though.

What does the tax code consider to be a bona-fide health insurance benefit?

As part of better defining the tax incentives / penalties above, the tax code has also recognized several different standards of health insurance “quality”. These categories are not linear or mutually exclusive and would probably not be as confusing if we had less wonky lawmakers.

“Minimum Essential Coverage” (Defined by ACA)

At a minimum, your health insurance benefit has to cover all preventive services defined by the US Preventive Services Task Force (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/). These are things like preventive mammograms, colonoscopies, annual well-visits, child vaccines, and other things. Entire companies like Nourish are built on an interpretation of preventive care as including nutrition counseling (it is a bit of a stretch IMO to say this includes services provided outside of an annual well-visit if you read the actual law).

There was recently a very interesting Supreme Court case questioning the constitutionality of the Preventive Services Task Force.

“Minimum Value” (Defined by ACA)

A plan has minimum value if it is expected to pay at least 60% of all healthcare expenses incurred by its members. This is an incredibly squishy number. The standard definition of a Bronze plan on the ACA is that it covers 60% of claims (Silvers cover 70%, Gold 80%, and Platinum 90%).

“Affordable” (Defined by ACA)

A plan is deemed affordable if the employee-share of premiums for a silver-grade policy are less than ~9% of their salary.

The above diagram is a map of the penalties and advantages available and proposed for employer health insurance.

Employers that are 50+ employees but do NOT offer Affordable coverage of at least Minimum Value are subject to penalties (see here for further explanation)

Small businesses that offer Affordable coverage at a Minimum Value are eligible for Small Business Healthcare Tax Credits (see here for further explanation)

The first draft of the BBB included tax credits for businesses that used an ICHRA to fund benefits (however this was not included in the final bill).

It is also worth noting that tax-advantaged health plans cannot cover anything they want to cover. Instead, expenses have to be roughly “healthcare-related”. These fees include the cost of purchasing and managing the plan (broker + TPA fees) but in general cannot include expenses for non-healthcare benefits provided to enrollees.

It would be tax fraud for a company to offer a rent-benefit whereby it paid its employees rent through its health plan (thus helping employees skip on taxes).

The definition of “what is healthcare” does in fact keep changing and is in general expanding due to the pressure of special interest groups. Remember that Medicare did not cover prescription drugs until 2006 and even a generation ago the idea that mental health therapy should be considered healthcare would have gotten you laughed at (most of the world would still find it particularly American to be entitled to therapy). The crazy thing to note is that it is essentially tax policy that defines what healthcare and health insurance are through these standards.

Another sidebar: you might notice that HSAs do not fit neatly into this picture. They are a great example of a healthcare product that was created in a legal gray area and then lobbied into existence. The law views HSA contributions as essentially money that contributes to the richness of your benefits and this interpretation is why HSA funds are able to be invested and spent with such tax-advantages (thank the valiant health insurance lobbyists of Unitedhealth for their lobbying effort after acquiring Minneapolis-based Definity Health in 2004).

Final sidebar: A lot of people think health insurance being provided by businesses is necessarily bad. I actually disagree. Reasons for this will have to come in another blog post but it boils down to two reasons:

Employers are one of the only “natural groups” out there, and the concept of a natural group is necessary to efficient insurance underwriting. The only reasonable alternatives to group insurance in the US are (1) fully government run insurance which would be a fiscal and bureaucratic disaster and (2) a return to the pre-ACA days where some people were uninsurable. Employer insurance provides a market-friendly way to get essentially guaranteed issue insurance. That’s not worth nothing.

Your company actually is responsible for a lot of your/your family’s livelihood and health. Workers Comp existed well before health insurance and probably everyone agrees this should be related to your employer. If you want a fun rabbit hole check out our other blog post on the inventor of Workers Comp insurance regulation, Franz Kafka /blog/franz-kafkas-insurance-careers.

Section 2: How do businesses provide these benefits?

Section 1 was all about “why” businesses provide insurance and which grade of insurance gets you what advantages / penalties from a tax perspective. This section is the “how”. What entities and financial vehicles and contracts are needed to achieve group insurance?

Drumroll please. I am a few sentences away from mentioning ICHRAs for the first time.

There are essentially three ways to offer benefits as a company that qualify for the tax benefits from Section 1:

Buy it. Companies can simply buy a “fully insured” group health policy.

Depending on the company size and the state they are in, groups have different options and marketplaces for buying these plans.

Companies pay a fixed premium and never get any money back. Usually companies don’t really even get data about how their plan performed. Money into a void.

Build it. Building their own health insurance plan (deemed “self-funding”).

This is where the company sets its benefits and hires a benefits administrator (like Yuzu Health) to manage their plan. See this blog post for more.

Technically the company is on the hook for paying all claims or getting stoploss insurance to help.

Build a bought version of it. Convincingly confusing contrived contortion? Yes.

This is where ICHRA comes in.

An ICHRA lets a company set policies around how employees can use company funds to purchase individual fully-insured policies and (optionally) receive reimbursements for other types of expenses.

I’ll do a little bit of a pro/con list for each of these options.

Type | PRO | CON | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Buy it: Fully Insured | Familiar option | “Devil they know” | ||

Build it: Self Funded | Usually cheaper Creativity Control and data | More complicated Having to make choices (“responsibility”) | ||

Build a Bought it (ICHRA) | Sounds fancy Choice without responsibility? Is that a thing? | More middlemen, more problems There is no choice without responsibility. |

I will admit, I’m a manual transmission guy myself and am heavily biased towards self-funding because I believe in the do-it-yourself show-me-everything approach to cars, life, and insurance. You will feel my bias in this article. But without bias, I would be an unopinionated chat bot. You’re free to open a new tab and try to understand ICHRA that way if you want.

Note: Only recently under Trump’s IRS were ICHRAs created as an option for businesses that wanted to receive the tax benefits described in Section 1. For a history of ICHRA written by a writer (not a customer service professional like myself) see https://thatch.ai/blog/the-story-of-ichra.

Section 3: The Guts of an ICHRA

Section 2 introduced ICHRA as the “build a bought version” of insurance. Let’s unpack this a bit because I actually do want you to understand ICHRA even if I don’t think you should touch it with a ten-foot pole.

Definition / Usage

“ICHRA”.

“Bless you”.

“No, I didn’t sneeze”.

ICHRA = Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Account (“ick-rah” / “the ick”).

Example usage: “My employer gave me the ick.”

Evolution

Legally, an ICHRA is an evolution of the older tax-vehicle, the trusty HRA (Health Reimbursement Account). Traditional HRAs that pre-date ICHRAs (themselves a special type of HRA) allowed and continue to allow employers to reimburse some qualified expenses that might otherwise be subject to a member’s deductible. Essentially a traditional HRA is a small self-funded wrapper around a fully-insured plan. If you don’t know much about HRAs it’s because they didn’t really change healthcare that much.

HRAs are typically structured as defined-maximum contribution policies. Members in a traditional HRA are allowed to submit up to some dollar amount of claims that their employer will help them cover that are not covered by the company’s insurance plan.

Extending the idea of an HRA, ICHRAs essentially allow for companies to go all-in on this wrapper account, having employees choose their own insurance plan and pay those premiums with the funds the employer sets aside in the ICHRA from this defined maximum contribution.

There are a few configurations that a business can set up with ICHRA in terms of what they want to cover with those defined contributions.

“Premium-only ICHRA”. A premium-only ICHRA says that the only types of expenses reimbursable by the ICHRA are expenses put towards premiums.

Note: this can be paired with an HSA if you also set up a Cafeteria Plan as another legal wrapper (barf this complexity, thank you lawmakers and tax lobbyists).

“Spending Account ICHRA”. This allows for the ICHRA to cover medical expenses subject to deductible or not covered by the health plan.

Note: these can not be paired with an HSA since HSAs do not allow anything to be paid for pre-deductible. Except I guess now telemedicine (in the recent BBB).

Diagram

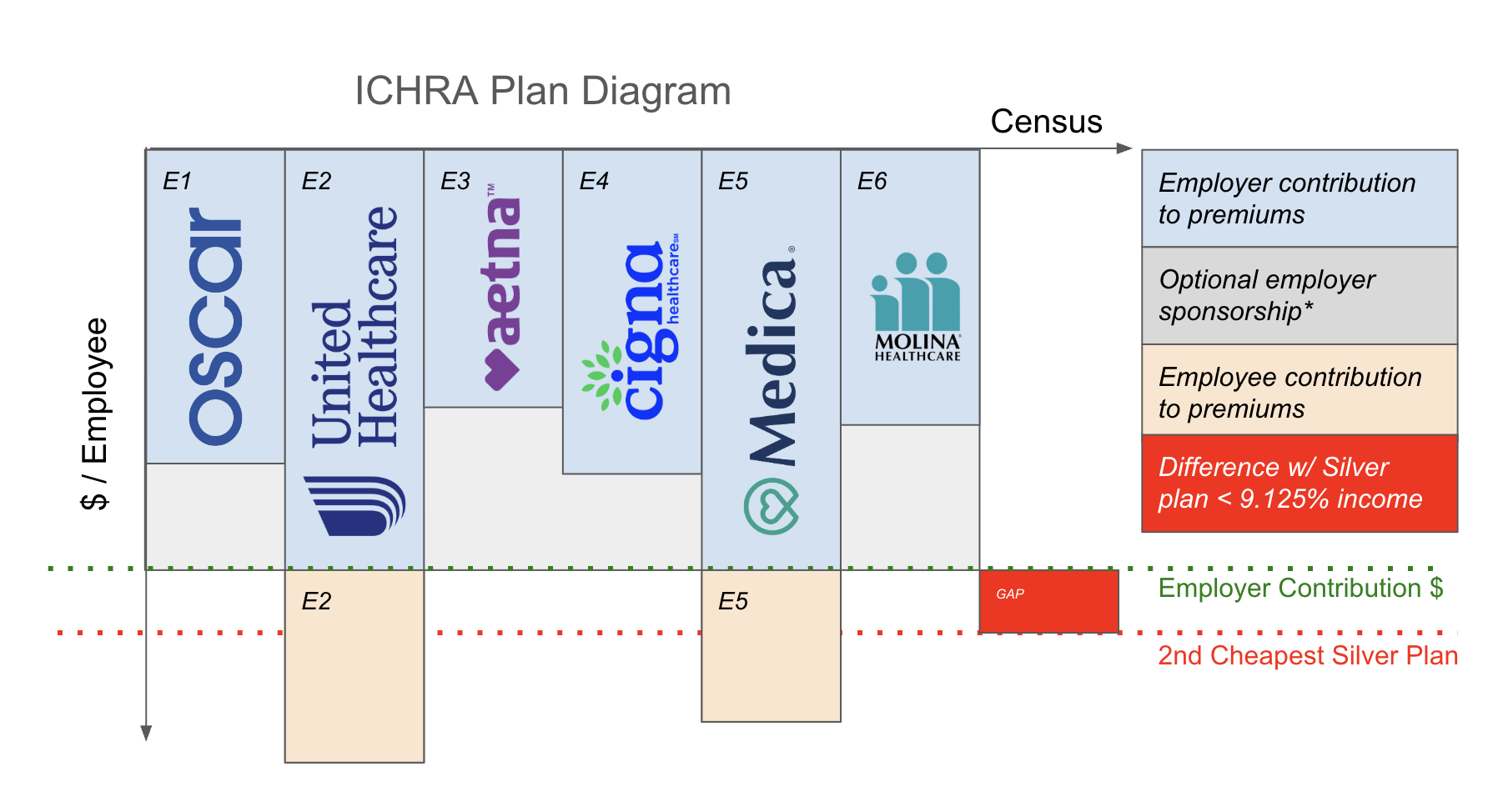

If you understand the below diagram, you pretty much can visualize an ICHRA.

The green dotted line is the “employer contribution”. It should be thought of as a monthly allowance.

There are specific rules about this allowance. In the EE tier (employee-only, no dependents) it has to be at least enough to be “affordable” defined relative to your employees’ incomes and the cost of the second-cheapest Silver plan (red dotted line) in your market. I guess the second-cheapest Silver plan is what the government considers to be “good enough”. We talked about the concept of Affordability earlier, in Section 1.

Allowances are allowed to vary by bonafide employee classes, geography, and family size. This makes for some fun spreadsheets for the broker class.

Employees might choose to buy a plan that is more expensive than their employer contributes. This is fine. This orange shaded area is just the employee contribution amount in the diagram.

If the company has a “Spending Account ICHRA” setup, they are able to use the shaded gray area to reimburse allowed medical expenses. And employers are able to define what they want to be “allowed”.

You might ask: how do employees get an individual policy for themselves and their dependents? This depends on the state in which they live. The good news is that the Obama administration made really good resources for individuals to shop for and buy individual insurance policies through https://healthcare.gov so people should have no issues with this.

The ICHRA “Product”

That’s pretty much all you need to know about ICHRAs. Understand that diagram and read a few technical rules about constraints and you’re ready to go. You can self-administer an ICHRA and it’s actually not that hard because even though you can go bananas on configuring things like custom contributions by employee class, age, geography, etc, most companies really do not need or want to do that. Simple works too. There’s kind of only one way to do it if you want your ICHRA to be HSA-eligible, which for white-collar companies with healthy employees is often a no-brainer.

I wrote a guide on how to self-administer an ICHRA for your business: https://vienna.earth/plate/russell/skip-ichra-middlemen. I personally self-administer our company’s HSA-compatible ICHRA and we have had no issues and no recurring work (all internally automated). We only use an ICHRA because we cannot buy stoploss insurance in NY as a small business.

There are a lot of companies that have turned this ICHRA administration into a commercial product. These companies frustrate me. They compete with Yuzu for attention and talent, and they don’t solve any of the underlying issues with health insurance that keep me up at night. I’ll briefly explain what these companies do and don’t do so that as a potential software engineering applicant you can decide whether you think the product these companies are building is meaningful to you and worthy of your unique talents and gifts.

Products similar, no moat, not sure how they use AI but they say they do.

Here is how these companies work:

Allow the company to configure how much to contribute per employee. Subject to rules on affordability, employee classes, age, geography, family size etc.

Build an onboarding flow where members can understand and shop for fully-insured plans.

Integrate with HRIS / payroll system to deduct employee contributions from payroll, collect employee premiums, and automate eligibility. Pay premiums directly to carrier from this, and forward eligibility to save employees the hassle of signing up themselves.

Some layer of health plan navigation services (this is the “AI” part maybe?).

Maybe analytics? Not quite sure on what data, but seems possible.

Section 4: Limitations of ICHRA

There are three severe limitations with ICHRA-managed plans.

Limitation 1: No Control of Claims

When a company is on an ICHRA, members are completely on their own in navigating claims. You have decided to release your people into the hands of Big Insurance and the bureaucracies that subsume them. Some company owners do this on purpose: it’s easier to wipe your hands clean and just say “not my problem”. There is a scapegoat factor too: having someone external to blame can be convenient sometimes depending on your personal moral compass.

The ICHRA middleman company, even if they wanted to, would have just as little luck as you talking to a real decision-maker on your claims or learning specifics of plan benefits. This is pretty scary: it’s almost like someone selling you a car but being unable to do anything to help you fix the car if it has issues.

It’s whimsy to believe that this model is going to fix healthcare or even affect it at all when it is so far away from actually allocating healthcare resources. People hoping to inspire humility from insurance folks will often remind them that “an insurance plan is not healthcare”. That is absolutely true. But an ICHRA is not even an insurance plan and it’s hardly related to healthcare.

To contrast, in a self-funded arrangement, accountability and responsibility for claims decisions is more localized and companies can escalate issues or at least understand the level of appeals and noise that is happening in the plan.

Despite branding themselves as AI companies, ICHRA companies really don’t receive all that much data about the actual operations of the plan and won’t be able to help you make benefits decisions.

Limitation 2: Expensive

ICHRAs are expensive for two reasons. One, they do not “remove” any admin steps in the process of processing health insurance claims. They only add a step (and an expensive one at that, they charge >$30PEPM to move money around). Premium dollars paid to an ICHRA are still funding the same amount of utilization management, soul-sucking claims documentation, complicated network contracts, PBM shenanigans, and inefficient claim payments middleware.

The other issue that ICHRAs face is that since members buy insurance plans on the individual exchange, they pay the highest rate for a unit of coverage since the individual exchange has the worst medical risk profile (least healthy members) and is community rated or rated just based on age bands in an effort to get healthy individuals to subsidize unhealthy members on the exchange.

In general the price of self-funded insurance will be around 30-50% cheaper than individual exchange insurance plans and come with more options and customizability.

Limitation 3: False Choice

I would have more sympathy to ICHRAs if there was truly a diverse market of health insurance plans available to people, but the economics of the individual market is dependent on government subsidies and tax breaks which means the market is not healthy or innovative. Here are the subsidies keeping the ACA individual market alive:

Small Business Healthcare Tax Credit (part of ACA, expanded in 2014)

Status: currently in force and stronger than ever.

Individual subsidies (part of ACA, massively expanded in 2021 as a stimulus for COVID)

Status: currently in force, but set to expire at the end of 2025.

ICHRA tax-credits as part of the BBB

Status: did not get included in the BBB

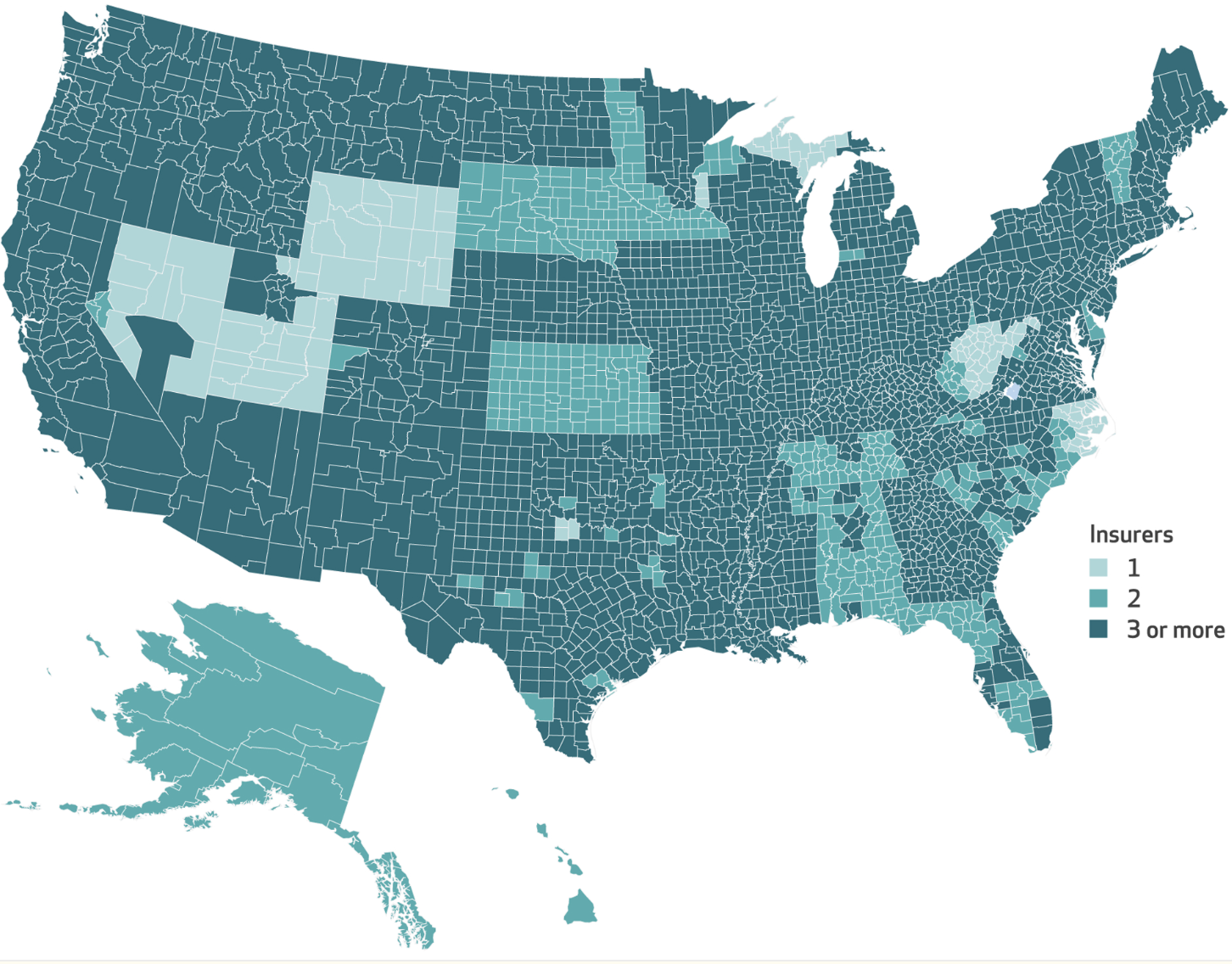

Without these expensive tax-breaks, the individual marketplace might not exist. Back pre-Covid there were year-over-year declines nearly every year in the number of plans available to people on the individual marketplace.

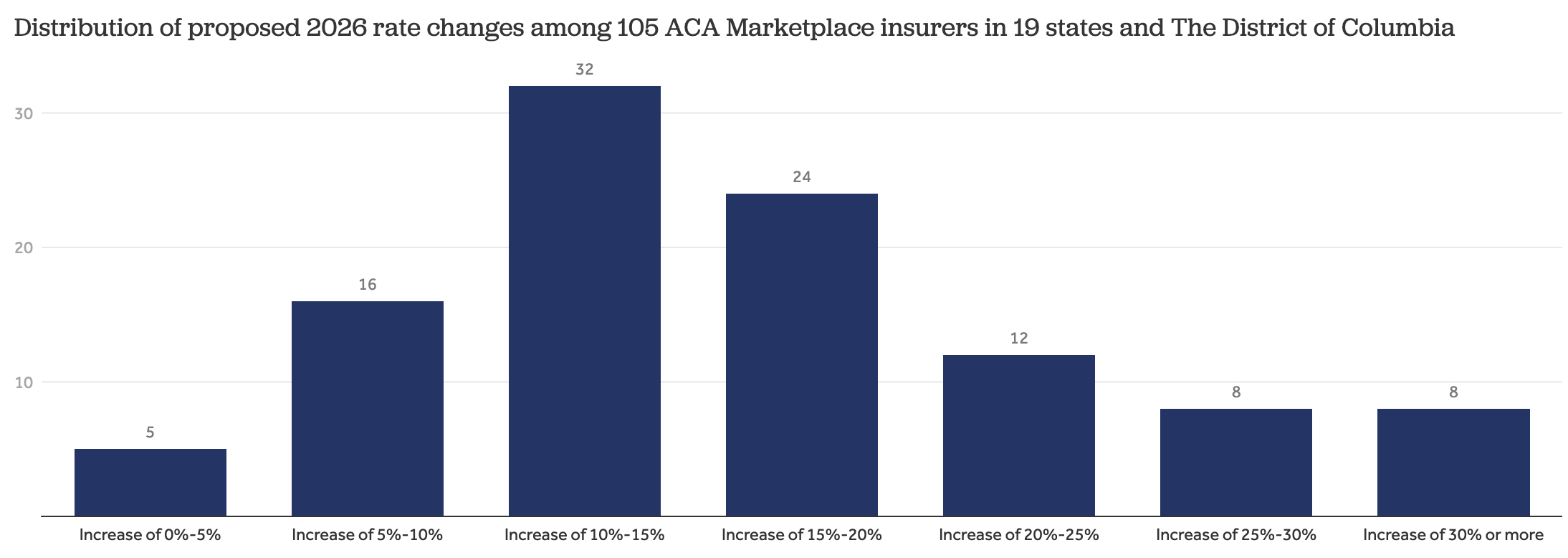

Now that Washington is thankfully not just doing whatever the Big Healthcare Lobby wants, we are seeing the tide come out on the ACA marketplace and carriers announcing massive premium increases to account for having to build an economically sustainable product without public subsidization. All of this limits choice available to members on ICHRAs.

The strategies that actually work at making health insurance plans more efficient (international pharmacy sourcing, Direct Primary Care, cash-pay) are not utilized in the ACA marketplace (exception: Mending fka Taro Health in Maine and Oklahoma) however each of these strategies are reaching maturity in the self-funded space which can move faster and make decisions without endless bureaucracy.

Thus the dwindling set of ACA plans that members on an ICHRA can pick from are all essentially converging on the same benefit structures: narrow networks, managed care, high deductibles. You can see members’ frustration with this discussed on numerous forums online.

Philosophical Close

Part of the reason that ICHRA is a wonky product to me is that it is based on the premise that insurance should be an individual product and individuals should be able to choose an insurance plan that works best for them. Healthy people can choose a cheap plan, unhealthy people choose a rich plan. Sounds great in theory.

However, this doesn’t really work on a macro level. At the macro level, society still needs to find a way to balance the needs of healthy and unhealthy people, lucky people and unlucky people. That’s what insurance is, it’s sort of like a referee or government policymaker coming in and deciding the boundaries and rules for how diverse people can collaborate to finance taking-care-of-each-other. There is really no free lunch, but there sure are a lot of people queuing in line for free lunch. If you listen to the brokers actually diving into ICHRAs deepest, it’s those who are trying to find a way to split groups by risk profile and strategically unload the unhealthy people onto the public marketplaces. It’s a zero-sum game, a tragedy of the commons accelerated by ICHRA.

Allowing everyone to perfectly match into a plan that works best for them causes a death spiral at the macro level that reduces options and consumer surplus for everyone.

Although it’s harder for companies to actually make health insurance plan design tradeoffs themselves than it is for them to outsource that responsibility, the system functions better when these tradeoffs are made locally. While ICHRA increases “choice” by some metric for individual employees, it reduces the number of communities choosing the real product: health insurance plan designs (tradeoffs!!). Insurance plans are policies, and policies are chosen not by individuals but by communities of people.

The only way healthcare is going to improve is if we find some better plan designs. And ICHRA, by pushing everyone to the monolithic ACA-plans, reduces the number of plan designs out there. This is a shame because new plan designs can actually tackle real problems like getting members healthier and connecting them to healthcare with less bureaucracy and more accountability.

Shameless Plug: We are Hiring Software Engineers in NYC

At the time of writing, Yuzu has 10,592 active members on health insurance plans we administer. Oscar had >200 employees before it reached this milestone. Yuzu has 19.

We spend our time helping members find care rather than helping employers find tax loopholes. We don’t really do marketing, it feels inauthentic. We don’t really do sales, our partners are all growing and business comes to us. Our biggest issue is that we need more engineers.

We do not work with any recruiters or do any outbound hiring. Everything is inbound or based on warm referrals (~50/50 split).

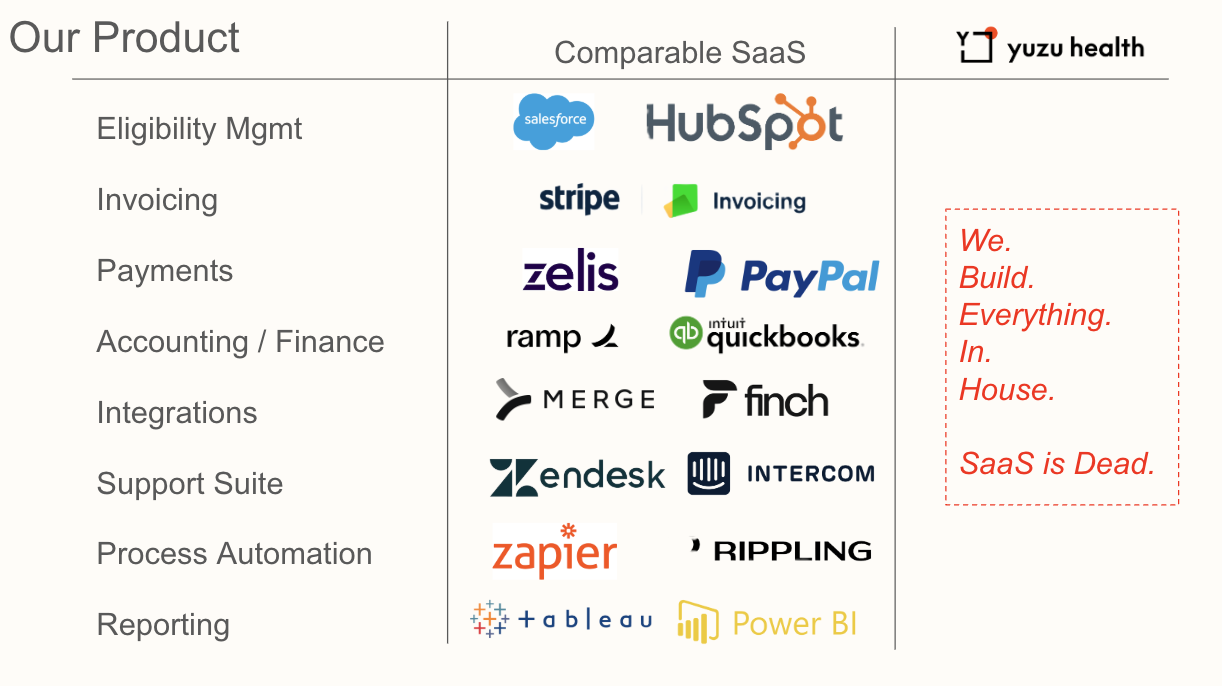

We have a top-tier engineering team and have built all internal and external software for our plans in-house. These are the products you would work on at Yuzu. SaaS is dead (this is the real impact from AI, not chatbots that tell you how to healthcare).